Grisel Sustache Flores takes a seat at a health clinic in Springdale, Ark., for low-income patients. The 46-year old Puerto Rico native says she learned last fall that she qualified for Medicaid, which Arkansas expanded under the Affordable Care Act to cover more adults. It would cost her only $13 a month, so Flores, who suffers from multiple sclerosis, eagerly signed up.

"My doctors in Puerto Rico say my condition is very difficult," Flores says through an interpreter at the Community Clinic facility. "Every day, it gets harder and harder."

She holds out both hands. "Today my fingers are swollen and numb," she says. "Some days it's hard to stand for long periods."

But in Arkansas, as in a handful of other states, Medicaid coverage now comes with some strings attached for certain beneficiaries. The Trump administration has allowed states to impose what's known as a work requirement. In Arkansas, that means Flores has to work, volunteer or attend school at least 80 hours a month and periodically file progress reports to prove she's doing so.

"Recently they have taken me out of enrollment because I was not reporting my hours of work," she says.

Flores says losing her Medicaid health coverage was devastating because she needs medicines and physical therapy to control her disease. "I cried. I cried a lot," she says.

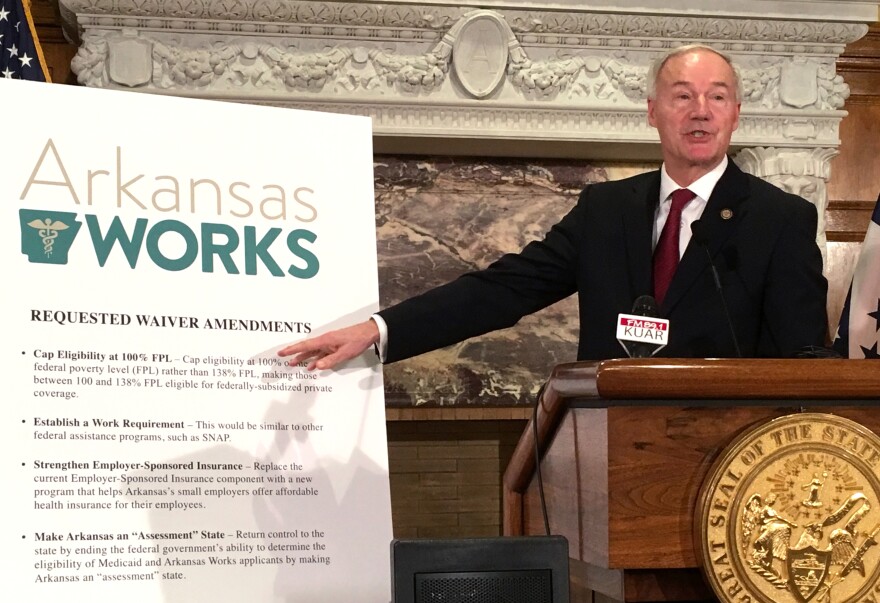

Community Clinic serves 37,000 low-income patients in the northwest part of the state. Irvin Martinez, its health insurance enrollment specialist, says he's witnessed a lot of turmoil among patients attempting to comply with the new Medicaid rules. In Arkansas, the program is called Arkansas Works.

Using his keyboard, Martinez opens the Arkansas Works web portal and clicks on some arrow icons. "I've actually seen, when I've logged into the website with them, that they are being locked out of their accounts if they enter the wrong data," he says.

Patients who are locked out are instructed to call a hotline to help them complete their paperwork.

"But that has problems, too," Martinez says. "I had one patient call and he was given the number to a prison, then to a private home. It took him three calls to the call center to get access to his account."

In August 2018, a month after the work reporting requirement took effect, the state Department of Human Services said there were 265,223 total enrollees in Arkansas Works, with more than 62,000 of them subject to the new rule. By December, more than 18,000 had been disenrolled from their Medicaid insurance because they didn't meet the requirement.

In response, DHS says it has beefed up its call center and is doing outreach to locate beneficiaries who might have lost insurance — by phone, email and home visits. The department has also launched an awareness campaign with paid advertising on public transit systems across the state and in college newspapers reminding people they need to comply with the work rule.

The department does offer a "good cause exemption" for beneficiaries dealing with unexpected circumstances that make it hard to meet the work requirement. But Martinez says Arkansas Works private insurance carriers and local nonprofits have had to step up to help confused patients navigate enrollment and reporting.

"Before the Affordable Care Act, nearly half of our patients were uninsured," says Kathy Grisham, CEO of Community Clinic. "Many resorted to local emergency rooms for free health care."

More people got insured when Arkansas expanded Medicaid. But Grisham says this new work requirement poses a serious burden on patients — and the providers who serve them.

"People do freak out when they find they are cut off," she says. "So we shift them to our uninsured population because we are obligated to take care of them."

Robin Rudowitz, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, says a few other states have also been approved by the Trump administration to test expanded Medicaid work rules, but those experiments cost money.

"We know Kentucky had done some original estimates that were in the range of $375 million to implement their waiver over two years," she says.

Arkansas has spent $7.5 million on startup costs, according to the Department of Human Services.

But Gov. Asa Hutchinson, who initiated Arkansas Works, says the program is a success. "We've already had more than 7,000 Arkansas Works participants who have moved into work," he says.

People disenrolled from Arkansas Works failed to comply, according to the governor, who says the work rule instills responsibility among certain Medicaid recipients who need a push.

"We are simply saying if you are able-bodied and able to work, and you don't have dependent children at home," he says, "you ought to either be working or you ought to be in school or you ought to be volunteering or contributing."

Hutchinson says Medicaid case closures are often the result of churn — people moving away, earning too much money to qualify or securing health insurance elsewhere.

"There's not an increase in uncompensated care," he says. "There is not a huge flock of those coming back and re-enrolling this year, so I think we are seeing that the system is removing people who have been ineligible for the service."

But KFF's Rudowitz held anonymous enrollee focus groups and says enrollees reported steep learning curves in following the rules.

"The rules are complicated and involve multiple steps to comply, and many who were trying to comply faced some problems such as creating these online accounts or navigating the monthly reporting. They had problems with passcodes or couldn't get assistance or had difficulty accessing the Internet, couldn't find a computer, or were uncomfortable using a computer."

In Springdale, Flores was able to re-enroll in Medicaid with the help of Martinez at Community Clinic. She pulls out her new insurance paperwork from her briefcase.

"My new documents have arrived," she says, "and I am learning how it works."

But Flores says she is now seeking counseling to help her cope with the stress of complying with her new health insurance.

Legal Aid of Arkansas, acting on behalf of nine Arkansas Works patients, has filed a lawsuit against the federal government over the regulations. The suit argues that the requirements are too cumbersome and cause harm to recipients.

Copyright 2019 KUAF