A library – full of books and knowledge – might not seem like the right place for propaganda. But the Onondaga Central Library has just opened an inaugural exhibit of WWI and WWII propaganda posters on its third floor. Librarian in the local history and genealogy department Barbara Scheibel says the more than 400 posters were in various sizes and conditions after sitting in storage for the better part of three decades.

"We have posters from France, Czechoslovakia, from China. We have all sorts of different countries represented. It's truly a wonderful collection."

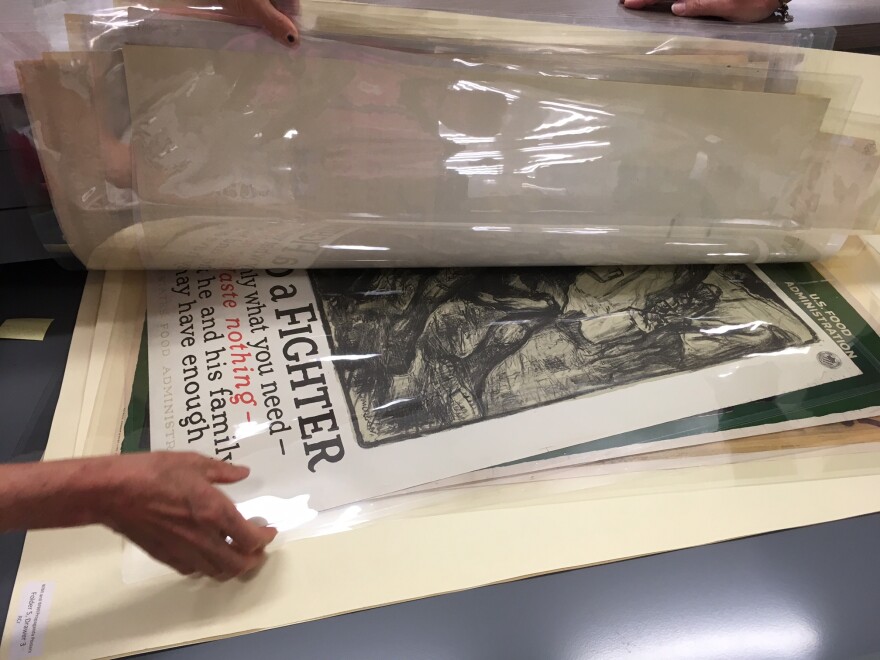

She says they’ve spent the past three years cleaning, repairing, and encasing the posters in mylar to preserve them and make them available to the community. They’ve also been inventoried to make them easier to find. Research librarian Kara Greene says the posters pre-date radio, TV, and certainly social media.

"There wasn't a single communication vehicle to get people to rally behind like you could today. People just lived in their neighborhoods and knew what was happening around them. They had newspapers, of course. But they didn't have the visual impact and the singular, 10-word message. Posters were already being used as primary communication."

The messages ranged from urging people to grow their own food, conserve oil, and buy war bonds…to more threatening warnings about how careless words could be picked up by spies on U.S. soil.

"You could mass produce them cheaply. You could use a graphic message, which is important today... Facebook or Instagram...it's all about the picture...much more than a newspaper article stating everybody should help the war."

Greene says one especially provocative poster asks citizens to “Beat Back the Hun with Liberty Bonds.”

"The photo is of a very monstrous looking solider that almost doesn't look human. He has green eyes...he just looks deathly terrifying. That was meant to represent the enemy, specifically the Germans."

She says this is around the time the word “hun” evolved from meaning a great warrior to something much more negative.

"The hun gradually became to mean that you have no mercy, that you would kill women and children, that you have no ethics, that you don't follow the rules of war. That made it easier for people to view everything happening during the war as just."

Greene says the librarians were concerned that the word’s perjorative connotation might be offensive to some. But in the end, they decided it was important not to censor it in favor of understanding the context. The exhibit runs through September, though patrons can look through the collection anytime at the library or learn more at onlib.org.